Germany's Nuclear Phaseout

A majority of the German public is in favor of a complete phaseout of nuclear energy generation in the country, which often comes as a surprise to those from Canada and the United States where nuclear makes up about 15% and 20% of power generation, respectively. However, the aversion to nuclear energy generation in Germany dates back to the 1970s and is a significant aspect of their Energiewende.

This primer will detail the history of Germany's aversion to nuclear power, the timeline of its phaseout, and the current status of nuclear power.

Nuclear Aversion in the 1970s-1980s

2000, the beginning of the phaseout

After Fukushima (2011)

Present Day: The Traffic Light Coalition and the War in Ukraine

Nuclear Aversion in the 1970s-1980s

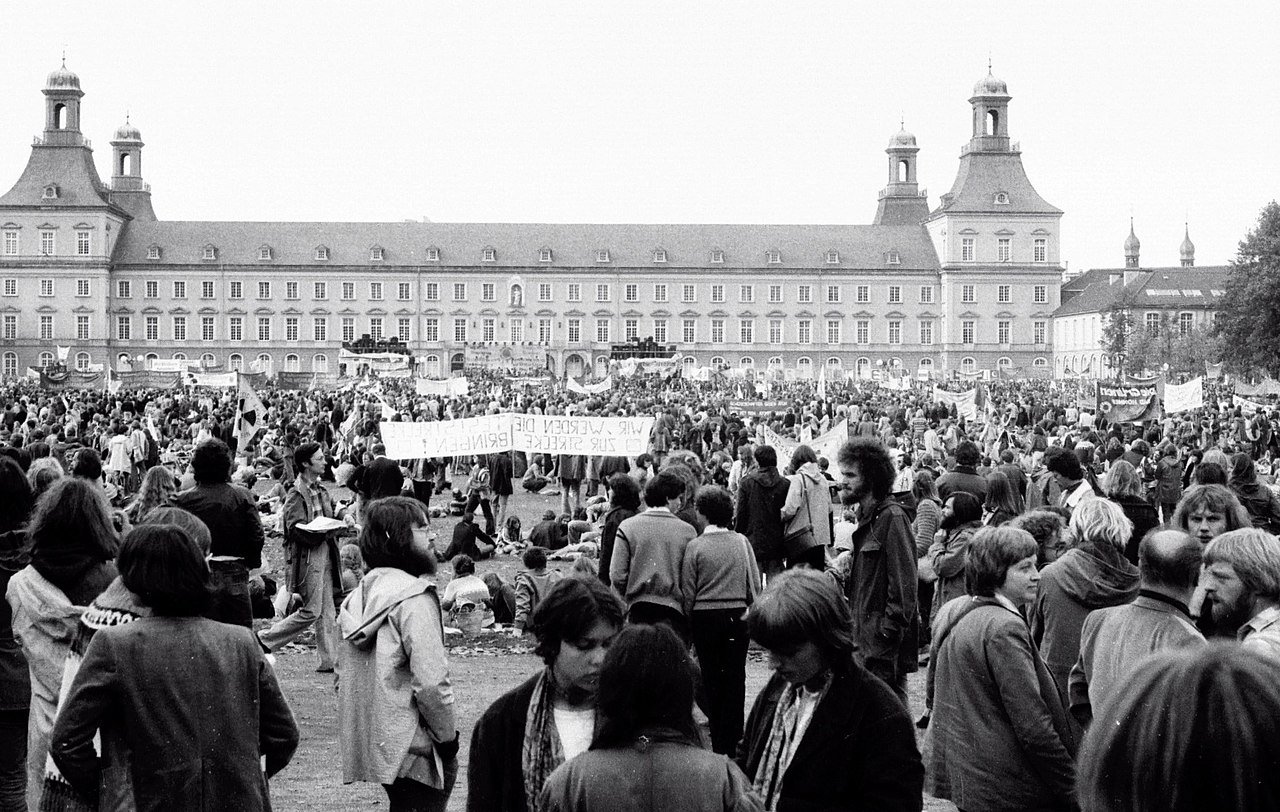

The pushback against nuclear power in Germany began around the 1970s as oil prices rose and nuclear became a more affordable option for domestic energy needs. However, many people protested nuclear energy projects due to concerns of environmental and health risks from increased radiation exposure around power plants, unsafe nuclear waste disposal and the risk of disastrous nuclear accidents. Throughout the 70s, the movement continued to grow and large crowds of protesters would occupy building sites of nuclear plants to protest their construction. In 1975, 28,000 protesters challenged the construction of a power plant in Wyhl, causing it to stop construction. In Hannover and Bonn, 200,000 people marched to protest the use of nuclear power after an accident at the US nuclear power plant, Three Mile Island. The movement against nuclear power was also one of the driving factors for the formation of Germany’s current Green Party.

The aversion to nuclear power by the general public only increased after the nuclear disaster in Chernobyl in 1986. Politicians at that time stressed that nuclear power was merely a ‘transient’ technology and no new nuclear power plants were built after 1989.

The phaseout begins?

In 2000, the SPD-Greens coalition government at the time, reached a “nuclear consensus” with the big German utilities to limit the lifespan of the existing nuclear power stations to 32 years and new nuclear power plants were banned altogether. The agreement was codified into the updated Atomgesetz (Nuclear Energy Act) in 2002 and two plants (Stade and Obrigheim) were taken offline in 2003 and 2005.

The CDU/CSU-FDP coalition government, elected in 2009 and led by Angela Merkel, extended the operating time for seven plants by eight years and 14 for the remaining ten. This move was known in Germany as “Ausstieg vom Ausstieg”, meaning “phase-out of the phase-out”. Approximately 40,000 people took to Berlin to protest this decision.

After Fukushima

After the nuclear disaster that occurred in Fukushima, Japan on March 11, 2011, the same government that had extended the lives of all the nuclear plants, decided to suspend the extension, following the tragedy.

At this time, public support for nuclear power was on the decline and the tragedy coincided with the state elections in Baden-Württemberg. After 58 years in power, the CDU government was under threat by the Green Party (which eventually won the state).

After three months of discussions, the Bundestag voted to phase out atomic energy, by the end of 2022. This led to a lawsuit initiated by major energy companies suing the government for damages, arguing that their investments were affected by the decision and residual electricity volumes that can no longer be generated. After ten years of negotiating, energy companies agreed to a settlement of €2.4 billion, footed by taxpayers.

In 2012, a year after the initial announcement, the Bundestag voted in favor to shut down eight plants that year and limit the operation of the remaining to 2022. Three plants (Grafenrheinfeld, Gundremmingen B, and Philippsburg 2) shut down in 2015, 2017 and 2019 respectively.

The Traffic Light Coalition and the War in Ukraine

The traffic light coalition government was elected in 2021 with aspirations to phase out coal and nuclear power in Germany, including the shutdown of all remaining nuclear plants.

The coalition issued the shutdown of three plants (Grohnde, Gundremmingen C and Brokdorf) on 31 December 2021 and scheduled the remaining for the end of 2022 – a complete phaseout of nuclear power in the country. At this time, the Ministry for the Environment had stated it will “reject the inclusion of nuclear power” in the European Union’s taxonomy on sustainable investments.

In February of 2022, Russian invasion into Ukraine incited major disapproval of the government’s increasing dependence on Russian oil and gas. This prompted the government to announce its plans to end dependence on Russian fossil fuels, by the end of the year. This, and the subsequent EU embargoes, led to the Russian state halting direct gas deliveries to Germany, by the end of August 2022.

As the German government began to plan out its energy future without Russian oil and gas, it looked to other countries to secure new gas supplies and partnerships on sustainable energy projects. However, the war brought back debates on Germany’s energy supply architecture and politicians considered revisiting conventional sources of energy to help with the German winter.

The FDP advocated for a year extension of the remaining three plants, while the Greens wanted to maintain the December 2022 shutdown date. The government initiated several assessments to see if nuclear power could contribute to the energy supply during the winter and after months of debate, Chancellor Scholz decided in October 2022 to temporarily pause the shutdown of the remaining three nuclear plants and continue their operation until 15 April 2023 at the latest.

This topic-specific primer is an extension of our main primer on Germany, available here.

This page was prepared under the Transatlantic Climate Bridge project - which is supported by the German Federal Government. Its contents are the sole responsibility of adelphi and do not necessarily reflect the views of the German Federal Government.